Being Human

AI, robotics, the internet of things, machine learning and predictive modelling are the signature topics of 2017. It is however helpful to remember that most things are still driven by human nature, imperfect and largely irrational.

Human decisions are not the results of perfectly constructed algorithms but habits, emotions and cognitive biases, which make a less rational choice seem more appealing. I am always amused to see people who run in to work taking lifts or escalators rather than the stairs to reach the office. Or my favourite: people work harder for free if it’s for a cause than for money if it’s purely for a commercial gain. This is because when money is mentioned, people apply market norms and evaluate how much money is involved and if it’s a good deal or worth their time. If the money is too little, they will actually work less than normal because they feel they are being taken for a ride. However, when no money is involved, people apply social norms to the situation and work harder.

We judge ourselves by our intentions, but other people by their actions

Most people want to be good, live in a way that treats other people, society and the environment with care and respect. In surveys, 81% of people say they would make personal sacrifices to address social and environmental issues. And 67% say that it’s important that the brands they choose make a positive contribution to society.

However, sustainable brands don’t yet have the largest market share, and we all find ourselves engaging in unsustainable behaviours that have negative impacts. So, there is an intention-action gap. Why is it happening?

Social desirability and wishful thinking

First of all, when people respond to surveys, they suffer from social desirability bias (wanting to be liked), virtue signalling (they are good!) and wishful thinking (they have good intentions and ignore constraints). To overcome this, researchers need to use implicit research techniques, conjoint analysis or observational methods, rather than straight questions on attitudes and intentions.

I often use intent scale translation techniques, such as Juster’s probability scale to convert stated intent to likely action. For example, only 83% of those who state that “they would certainly purchase” an FMCG product actually do so, this diminishes for durable goods.

Decision-making is not linear

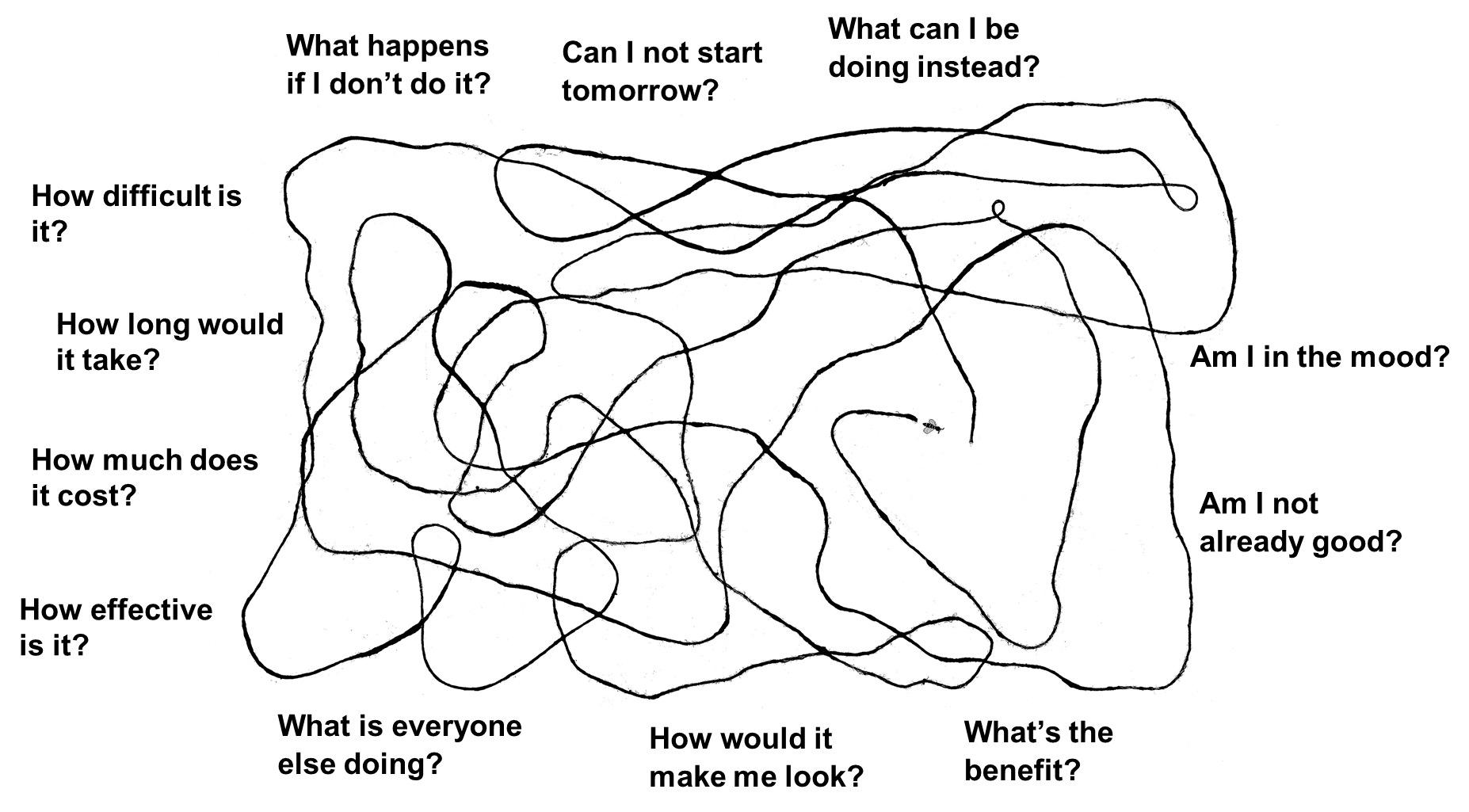

Thanks to the work of Daniel Kahneman, we now know that most decisions are not made by our rational brains. Two systems of reasoning, the rational and the intuitive, work in parallel. The rational system is slow and makes decisions based on careful consideration of facts and evidence. The intuitive system, on the other hand, arrives at a decision much more quickly and responds to subtle sensory cues such as familiarity, emotional reaction and mental images. Often, especially when we are multi-tasking, are distracted or under stress, the intuitive system takes over completely.

Decision-making is not a rational, linear, sequential process. It looks more like a path of a bee with a multitude of simultaneous questions arising and being answered within a second.

A good strategy to promote desirable actions or products would be to make them appealing to both, rational reasoning and the intuition.

Closing the intentions – actions gap. Let the fun begin

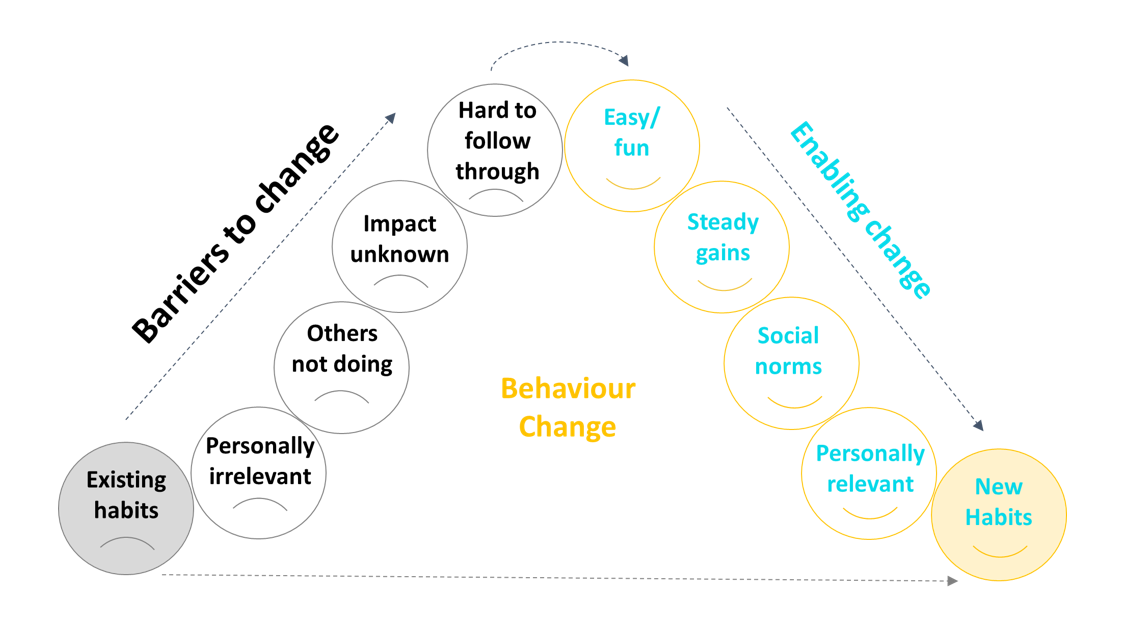

Apart from contextual and social barriers, there are many things within us that make it difficult for us to change behaviours:

– Existing habits: 40% of our actions are driven by habit

– We can’t immediately see how what we are asked to do is personally relevant

– We think that there is no point doing something if the others are not doing it

– We have a “present bias”, prioritising present benefits over future

– We find the ask too difficult and can’t follow through

To encourage behaviour change, start by making it fun, and follow a mirror image of the barriers – enablers of behaviour change.

I applaud the London Mayor’s initiative to clean up the city’s air through introducing toxicity charges for the most polluting vehicles and establishing an ultra-low emissions zone. It’s all very needed.

However, behavioural insight shows that people are conditionally co-operative. In experiments most people choose a smaller incentive to adopt a good behaviour vs a larger incentive for themselves, if it means that those not behaving in the right way are penalised.

Following our behaviour change model, the Mayor could:

1. Incentivise walking and cycling through deals with employers, retailers and entertainment venues to offer facilities and discounts to people arriving on foot or by bike.

2. Make walking and cycling fun. For instance, VW’s “The Fun Theory” campaign turned stairs into piano keys, resulting in 66% more people opting for stairs rather than escalators. Could we have cycle routes that make the best use of London’s creative talent?

Show that cycling is fun. To-date most use of behavioural science has been directed at showing how dangerous cycling is!

3.Make it personally relevant. Don’t talk about air pollution in London, but the “air you breathe”, “health in your area”, “safety in your street”.

4. Make cycling and walking a social norm: instead of pushing the message that ”most short journeys are done by car”, say “this year X% more people in your borough are walking or cycling instead of using their cars” or “your neighbours are driving less, are you?”. Introduce competitions between the boroughs, people are competitive by nature.

5. And finally, provide regular feedback, communicate small gains and achievements.

Recent advances in behavioural science mean that delivering change does not have to be daunting. Let the fun begin!